The exhibition The Liver Must Go to The Images brings together new works, which deploy printed matter as a sculptural material. Pictures pulled from various sources – including newspaper clippings, fashion magazines and art monographs – are broken down and built up into new image-objects wherein the partial obliteration of pictorial content becomes another mode of inscription.

Throughout the works assembled here, the surfaces of pages are entered into so that new spaces within the image are opened up. Careful incisions cut parts of the image away, or draw the surface out into three-dimensionality; and folds or collage elements are introduced to interrupt the flow of the image surface and set up new relations across it.

In a technique developed by Dicke more recently, sandpaper is used to rub away areas of the printed pigment, dragging the image towards the non-image of the blank page that facilitated its appearance, and occasionally puncturing that page with little holes that make its materiality more visible.

'Political Horizon', one of several large-scale sandpapered images in the exhibition, we are presented with the remains of a blown-up newspaper clipping. Underneath the radiant effacement of the image’s heavily sandpapered top half, we see a moment of tight embrace between two anonymous blue-suited men. In its initial context, this snapshot could easily pass us by as the sort of overly familiar image that we encounter without registering or remembering. But having been cut-out, scaled-up and partially rubbed away, it suddenly gives rise to a new appearance: the hands of one faceless uniformed male politician reach around the back of another, pressing into him with a flash of urgent intimacy. The two bodies are fully united in a split-second melodrama, with a tension that remains secret and off-script.

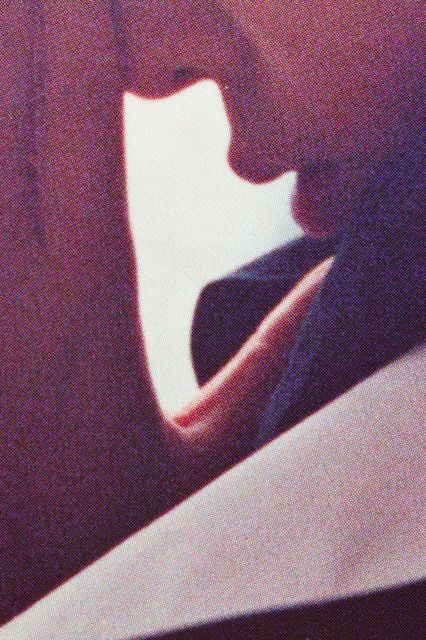

Other works in The Liver Must Go To The Images take the dematerialization of recognizable forms even further. In 'I Will Shape Myself', another scaled-up sandpapered print, we are met with the negative space that was shaped by part of the hand and facial profile of the figure in the original photograph. But with the rest of the photograph’s image surface now pulverized into non-depictive formlessness, this re-framed detail becomes a visible hole, as an absence with new presence.

While heads and faces are very often cropped out or rubbed off in Dicke’s processing of found images, fingers and hands will often be the parts that are left behind. Faces tend to prompt quick allocations of meaning; they suck the gaze in, demand categorization, and promise too much in terms of recognition, personality, and narrative. Hands, on the other hand, are often up to something else entirely – as evidenced by the range of peculiar shapes made by hands through-out Dicke’s works.

And hands have presence in this exhibition not only as depicted imagery, but also as traces of physical handling. There is an undeniably haptic quality here: these images do not exist as disembodied information; they are malleable materials that are encountered as sites of physical contact. These are surfaces that have been touched, and their status as tactile objects is affirmed by the shadows they cast, and the holes that frame the space around them.